Typefaces have always exerted a powerful force on my imagination. I grew up with huge, heavy American Type Foundry type sample books in our living room, and would spend hours looking at the designs. When I started to study typography and book design, I was fascinated by the history behind the styles we use, the people who created them, and the stories of how they came into being.

A few weeks ago I wrote about one of my favorites, Bembo, and used it to show how you can recognize oldstyle typefaces. I talked about how the original letterforms came from type designers imitating the strokes of a scribe’s square-nibbed pen.

Aldus, Francesco and Pietro Come Calling

But there’s more in Bembo’s DNA than the traces of calligraphers copying old Greek and Roman originals. Drill down a little more and another layer of cultural history falls open, with surprising connections.

The art of the printed book spread quickly for the times, moving from the innovations of Gutenberg around 1450 near Mainz, Germany, to other cities in Europe.

Aldus Manutius, a humanist himself, set up his Aldine Press in Venice around 1490. Aldus took as his symbol the image of a dolphin around an anchor, which is derived from the ancient symbol for Beirut, Lebanon. This same symbol, by the way, was used for many years as a logo by Doubleday Books. Aldus’s sign also included the latin phrase Festina lente, or “hasten slowly.”

Aldus was an entrepreneur and an innovator, and soon became the most prolific publisher and printer in Renaissance Italy. He invented pocket editions of books with soft covers that were affordable for a wide range of readers, organized the scheme of book design, normalized the use of punctuation, and used the first italic type.

If you recognize Aldus’ name, it may be because the company that created Pagemaker, the first widely used layout software, and that spurred the whole desktop publishing revolution, was named Aldus, and used his image as their logo.

Bembo Is Born

For the design of his italic Aldus turned to Francesco Griffo, who made the molds in which the type would be cast. Then Aldus decided he needed a new typeface that he would use first to publish an essay titled De Aetna by the famed scholar Pietro Bembo.

“In February 1496, Aldus published a rather insignificant essay by the Italian scholar Pietro Bembo. The type used for the text became instantly popular. So famous did it become that it influenced typeface design for generations. Posterity has come to regard the Bembo type as Aldus’s and Griffo’s masterpiece.” —Allan Haley, Typographic Milestones

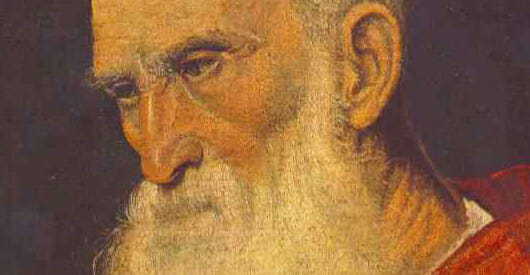

Bembo was a very well-connected cleric who was friendly with the Medicis and had an affair with Lucrezia Borgia. He influenced the development of the Italian language and assisted in the revival of interest in the works of Petrarch. Bembo was also instrumental in establishing the madrigal as the most important secular musical form of the 16th century.

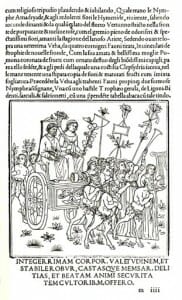

Griffo continued to refine the design of his roman typeface up until the publication, in 1499, of the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, (certainly one of the strangest and most mysterious books ever published in any age. This book, by the way, was the unusual centerpiece of the recent bestseller, The Rule of Four.) It is this design that has been known ever since as Bembo.

The Bloody End of the Story

Just as Aldus Manutius was about to achieve a government-authorized monopoly on the printing of Greek literature, he and Griffo had a falling out. Griffo left Venice for Bologna. The last notice we have of him is in 1516, when he is charged with beating his son-in-law to death with an iron bar. It’s thought he was hanged for his crime, a strange end to one of the most influential type designers of all time. To this day, italic fonts are known in Spanish as letra grifa after Griffo.

The design of Bembo was a clear attempt to bring the humanist script of the finest scribes of the day to the printed page, without slavishly following the more formal lettering of the day. It would later serve as the chief inspiriation to Claude Garamond, among others. Typefaces based on his work include Poliphilus, Cloister Old Style, Aetna, Aldine, Griffo Classico, Dante, and Adobe Minion.

Griffo has never received adequate recognition for his enormous contribution to type design. —J. Blumenthal, The Art of the Printed Book 1455-1955

So the next time you’re scrolling through your font drop-down list, think of the book designer. It’s not so much that all this history is present in his mind at all times, not at all. But in the meditative trance that settles over him as he lays out his book, the lines of Bembo flowing from line to paragraph, from paragraph to page, the ghosts of clever Aldus, suave Bembo, and doomed Griffo, the bloody bar still grasped in his hand, might rise, wraith-like, from the pages.

Even the prosaic act of flipping open the pages of a book can sink us into the accumulated history of western culture. Typefaces like Bembo are unique repositories of much of this history, encoded with mysteries within their subtle designs. It’s the province of the typographer to use each of these typefaces to the best effect for the book at hand. And with Bembo comes all its history, as alive today as it has ever been.

This article was part of a longer article originally published on Self-Publishing Review The picture of Cardinal Bembo is by Titian and is courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.