Do you ever wonder how the Plain Jane word processing files you turn over to a book designer or typesetter get transformed into the graceful typography and measured lines of a printed book?

Well, that process starts with the most basic and essential first step: file prep. And no matter how routine this step is, it can have a major influence on how well the finished book is constructed, and how efficient it is to lay out.

Follow the Steps to Clean Those Files

It’s likely the manuscript was examined in the bidding process, but once the book is actually in production and the designer has a truly final version of the file, it’s time to take a close and thorough look at the file.

This examination is going to involve:

- Analysis of the content hierarchy and the way the author has communicated that to the reader. This includes parts, chapters, subheads and other parts of the book intrinsic to its structure.

- Inventory of the formats used in the book. We’ll count up each set of formats and how they relate to each other in the typographic plan for the book.

- Perusal of the actual word processing files that the author has presented. We need to be working from the final files to do this properly, and we’re looking for the way the document was created, are formatting styles used, how “rough” is the manuscript?

But no matter what we find, the first necessary step in making the transformation from word processing files to book typography is cleaning up what’s been left in the files.

Over the years I’ve developed standard routines for handling lots of text quickly and efficiently. Most of these routines rely on Word’s powerful Find and Replace function.

It wouldn’t be too hard to write a whole series of articles about this function and the many ways it can be used to massage, clean, adjust and reconfigure massive amounts of text blindingly fast.

What I want to go over here is the basic manuscript cleanup that every book goes through before it gets transported over to the software used for book layout.

Necessary Steps, Necessary Order

It’s important to do these steps in a specific order, and I think you’ll see why as we go through them.

The first task is to take out all the extra spaces in the file.

Note: These instructions apply to all typographic material. If there are tables or similar elements in the book you’ll have to examine how they were created before you use these find/replace techniques. If possible, move the tabular material to a different file, then clean the remaining text before reassembling the file.

There’s a persistent habit that was born in the time of typewriters of putting two spaces between sentences. If you leave these in you won’t be happy with the result, and having two spaces between sentences is not going to make people think your book was done by professionals. Since the end of a sentence is already signified by a period and a space, no other spaces are necessary.

In the Find and Replace dialog, the space character looks the same here as in your file: you can’t see it unless you put your cursor into the “find” or “replace” field. So make sure you put 2 spaces in the “find” field and 1 space in the “replace” field. We’re telling Word to look for any occurrence of 2 spaces next to each other. This will also find instances of 3 spaces, 4 spaces, and so on, since it will continue to find any 2 spaces together.

The “replace” field tells Word to delete the 2 spaces and instead replace them with 1 space.

Starting at the top of the file, I run this first. Because of the way Word performs this task, you will likely have to hit “replace all” more than once to root all these extra spaces out. There will be hundreds of them.

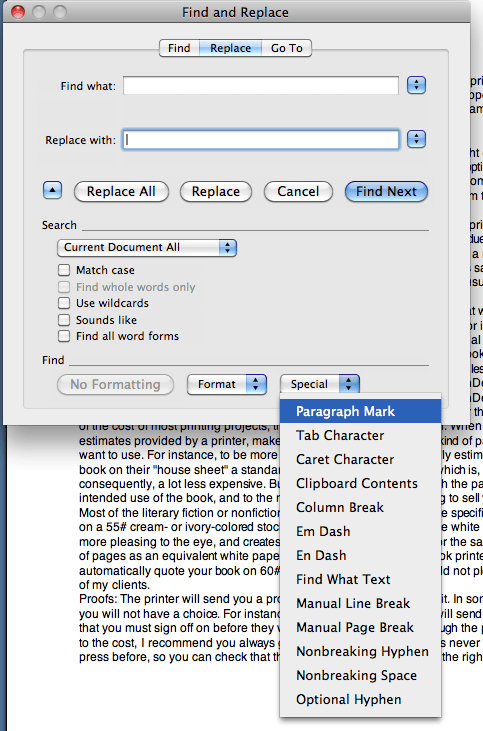

Note: You can access all of the codes that Word uses through the drop down menus at the bottom of the “find/replace” dialog. But if you know the few you’ll use regularly, it’s faster to just type them in yourself.

Next up is getting rid of other stray spaces. These are usually invisible in the Word file and seem inoccuous. But in page layout, all of these extra characters are a source of potential problems.

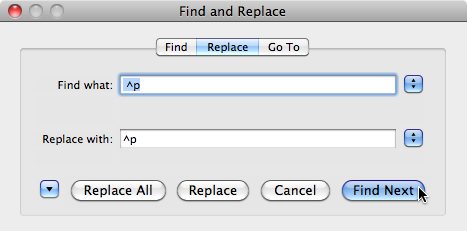

Our next “find/replace” will be for trailing spaces. These are at the ends of paragraphs, just before the end-of-paragraph marker.In the “find” field we’ll hit the spacebar and then enter ^p. (You do this by using the ^ character on the keyboard, shift-6.)

This code stands for a paragraph return, the end-of-paragraph marker. Every time this character occurs it signals another discrete paragraph. This will be important later in the process.

In the “replace” field we’ll put just the paragraph symbol: ^p without the space.

What we’re telling Word here is this: “Go look throughout this file and find anyplace there’s a space followed by a paragraph return. Delete both of them and replace them with only a paragraph return.” Because of the nature of this search you will only have to perform it once, and Word will report back how many instances have been changed.

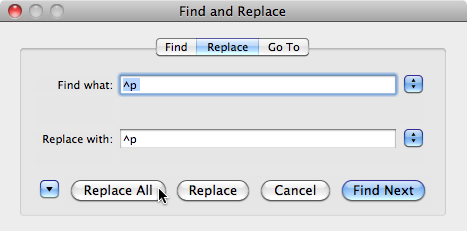

Next we’ll look for a related problem, spaces that have crept in at the very beginning of a paragraph. Although it sounds like this would be rare, it’s actually quite common.Here we’ll find ^p that is, paragraph return then a space, and replace with ^p thus leaving the paragraph return by eliminating the space.

The Problem With Tabs

We’re now ready to deal with the problem of tabs. Tabs stands for “tabular matter” and comes from typewriter days, when little metal sliders would allow you to return to the same spot on the page on subsequent lines.

If you open most book files and look at the codes you’ll find tab codes in odd places. Sometimes paragraphs are indented on the first line by the author hitting the tab key. Sometimes they appear at the end of a paragraph, as if they’ve gotten lost. And sometimes there are lots of tabs on what appear to be blank lines, like they’ve gone on a trip somewhere.

But in books we use tabs sparingly, and only for specific reasons. We never use them to indent paragraphs, or to position graphics or photos, or for many of the reasons people put them into their word processing files. I use tabs for:

- Tabular material including the Contents page and other simple charts or lists. More complex or extensive lists are better handled with a “table” function found in most layout programs.

- Some kinds of lists. For instance when we format Notes sections and want the note numbers to align on a decimal point (flush right) and the note following to align normally (flush left) on the same line, we can accomplish this with tabs.

All the rest of the tabs have to come out. And if you don’t have one of these cases where you do need the tabs, it’s faster and more efficient to simply take them all out of the file.

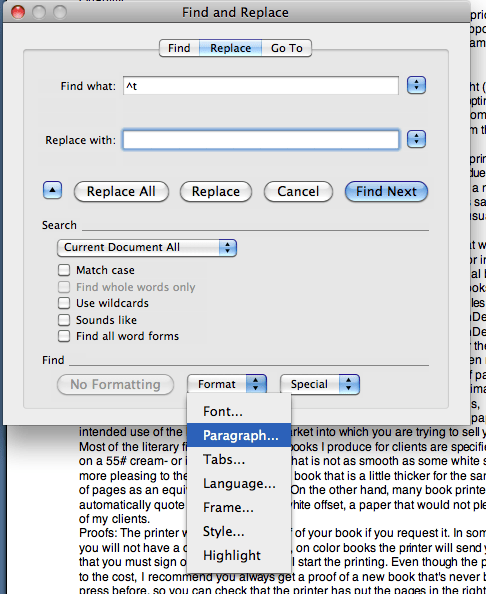

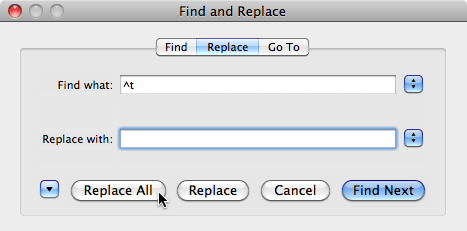

In the “find/replace” dialog we’ll use the code for a tab character ^t in the find box, and put nothing in the replace field. This turns the “find/replace” function into a “find/delete” function. It’s important to put your cursor into the “replace” field to make sure you haven’t left a space character in there from your previous operations. One click should remove all the tabs from your document.No More Extra Returns!

Now we’re ready for a final “find/replace” and this one is to get rid of the extra paragraph returns that are in the file.

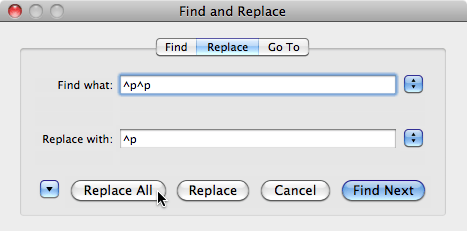

By now you can probably guess what we’re going to do. Here we see the very simple find ^p^p that is, two paragraph returns in a row, creating an unwanted and potentially troublesome extra line, and replacing them with a single paragraph return. You might have to run this one a few times to get rid of all the extra returns.More Fun with Find and Replace

All of the operations we’ve reviewed here are pretty simple once you know how to use the special characters, and you know what result you want to end up with.

But Word’s Find and Replace has a lot more power and utility than that. Here’s the list of “special” characters you can manipulate. Note the “Find What Text” and “Clipboard” options. these provide a lot of creative flexibility in manipulating your text files.

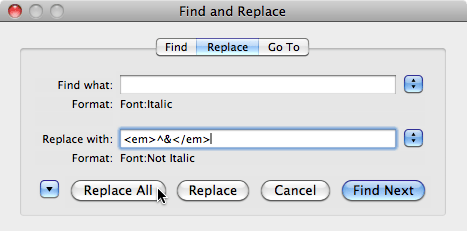

As a quick example, I had a document that had been formatted in Word with lots of italics for book titles. I wanted to move the document to HTML to use on a web page, but I wanted to switch the Word italics code for HTML. Find and Replace can do this easily:

Notice the formatting instruction in Find. It will find anything in Italic. The Replace uses the HTML codes for begin and end italics. In between is the “Find What Text” code ^& along with the instruction to eliminate the italic formatting. In one click every instance of italic will be de-italicized and wrapped in HTML codes.

Takeaway: Learning to use the Find and Replace functions in your word processor will make doing the necessary file preparation before book layout efficient and consistent.

Image licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License, original work copyright by j nelson, https://www.flickr.com/photos/32807937@N00/