By David Kudler

Like many of you, I am a complete fangirl of Joanna Penn, author of fiction and non-fiction, podcaster, blogger, and source of much, much wonderful information regarding the joys and challenges of being a “guerrilla” indie author/publisher.

At the beginning of the month, I was delighted to listen1 to her interview with Dave Chesson, who, in addition to being an indie author himself, is the creator of the wonderful Amazon keyword research tool KDP Rocket. They talked about his experiences as a self-published writer (which he has blogged and podcast about extensively at kindlepreneur.com), and about his reasons for creating KDP Rocket.

Imagine my delight and surprise when, as part of their extended discussion about Amazon and keywords, they referenced my article last month, Words Gone Wild!2

Their discussion was intelligent and thought-provoking, looking at the best way to select keywords for your book. I particularly appreciated the response to my article where they looked at the difference between “keyword stuffing” and “natural phrases” — what they called long-tail keywords.

It got me thinking.

Hypothesis: Natural-phrases are better in Amazon keywords

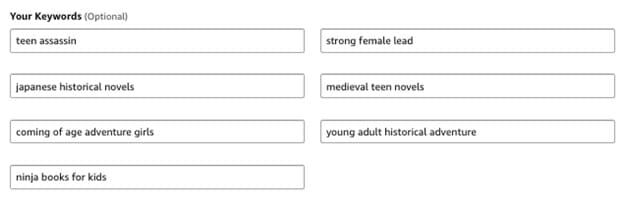

One of the things that I had assumed when I wrote that post — not based on data, but on a general sense that it must somehow be right — was that human-readable, natural phrases, ones that an Amazon customer might actually put into the search box, would be more relevant — that is, that by putting an actual phrase in your KDP keyword fields exactly as a reader would enter it into the Amazon search box, your book will be more likely to appear at the top of customers’ searches. Which is what we all want, right?

That’s why I was surprised (as I said last month) to find that adding words to your keywords fields and eliminating redundancies actually improved my book’s results in searches — and therefore sales.

Now, I am, for the most part, a one-person shop — time spent researching keywords and algorithms, while important, is time not spent writing, editing, designing… In other words, I couldn’t think of a quick experiment like the one my still-unnamed friend and I came up with at WorldCon3 that would show that having the complete contents of one of your fields exactly match the customer’s search term would make your keywords more effective.

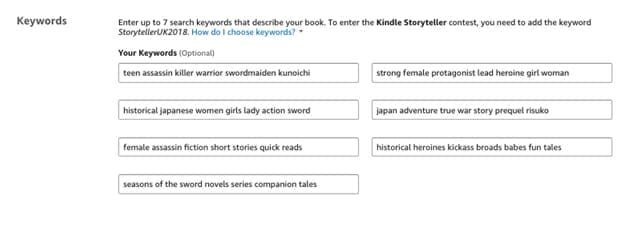

But like Joanna and Dave, I assumed that this was in fact the case. As such, I made the choice to include as much natural-language phrasing in my keywords as I could quickly come up with. Only then did I use any remaining space to pull in variant keywords (i.e., Asian instead of Japanese or female instead of girl) and other words and phrases that I’d earlier dismissed as a) possibly less relevant and b) less effective.4

Working with the Amazon API as he does in developing KDP Rocket, Dave is in a much better position than I to test those hypotheses, and so it was extremely interesting hearing his thoughts in the podcast.5

Testing the Hypothesis: Does search phrasing matter?

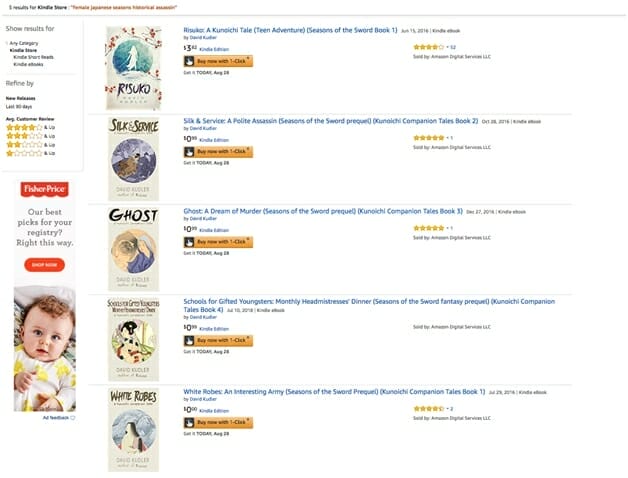

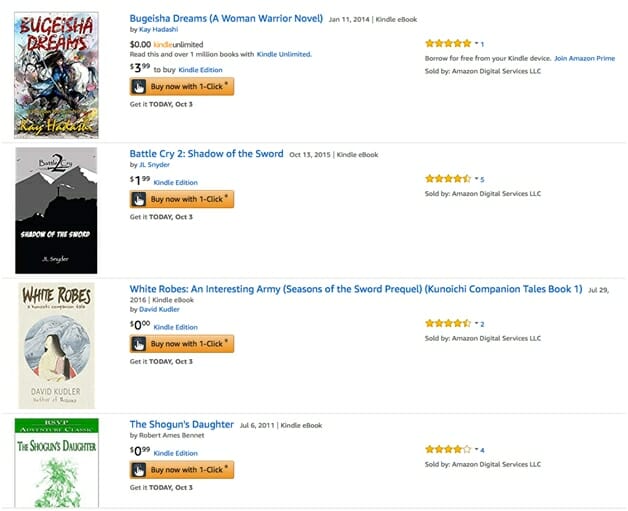

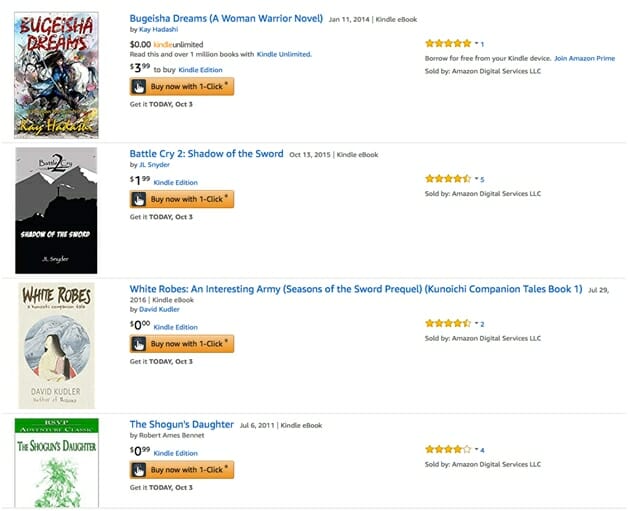

So, based on their conversation, I decided to revisit my experiment — without changing any keywords. You’ll notice that in my first proof of my theory, my rather un-natural search (female Japanese seasons historical assassin) was in fact a perfect fit for Seasons of the Sword, my series of historical books on teen girl assassins in medieval Japan. Only my books showed up, which was gratifying; however, White Robes, the title on which I first conducted the experiment, showed up last of the five books.

So, without changing the keywords in White Robes, I ran a search on the exact contents of one of its keyword fields — the very last one: seasons of the sword novels series companion tales. Still not exactly something someone’s likely to type into the Amazon search box, but possible.

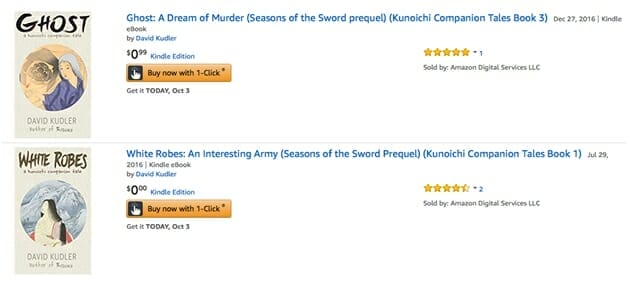

When I did that, only two of my titles showed up — but again, nothing else did. Neither did the other three titles in the series. So clearly using the exact phrase did narrow things down. But my test case, White Robes still didn’t show up first!

Not only that, but the one that did, Ghost doesn’t even have any of those keywords in its keyword fields!

It does, however, have the words in the search term in its subtitle, series, and description fields. (The other titles in the series have bits but not all of the search term scattered through their metadata, so they didn’t appear on the search at all.)

This of course reminded me that the phrases that appear in those public metadata fields will greatly increase your book’s relevance in a search on one of those phrases, since Amazon appears to search those metadata fields before checking the keywords or categories that you’ve added. I assumed that that was why Ghost appeared before White Robes in my second experiment.

What I learned from this: when customers search using longer phrases, Amazon’s search engine is (surprise!) much more selective. It won’t return anything that doesn’t include all of the phrase.

What it didn’t show, however, was that an exact (or near) match of the contents of a keyword field was more likely to be relevant — unfortunately, the fact that both books had the search terms in their subtitle and series fields trumped what was in the metadata. Grr. Shouldn’t have chosen that set of keywords to test on.

Further Refining the Hypothesis: Does search word order matter?

So, back to the drawing board. For search #3, I used another one of the keyword fields for White Robes: historical japanese women lady action sword. This search returned four books — only one of which was mine: White Robes. There we go!

In these search results, my book was third. Why? The two ahead of it and mine all had the word sword in the subtitle (the fourth-place title didn’t). So they were even in that regard; why were the other two ranked above mine?

- Mine has a higher Amazon sales rank, so it wasn’t that. They’re older than mine, so it wasn’t that.

- None of the books included historical, japanese, women, or action in any of the public metadata (title, subtitle, series, or description).

- All, including mine, had those words scattered through their listed categories.

- White Robes, however, is, unlike all of the other titles, permafree. Hmm.

So why didn’t my book, which has the exact search phrase in its keywords, show up as the most relevant title for that search?

I tried changing the order of the search term: lady action japanese sword women historical. The same four titles showed up in the same order.

In fact, the same result showed up no matter the order I put my search term in.

So clearly, phrasing is less important than that all the words in a particular search be present in a book’s keyword (or other metadata) fields.

To test the question of phrasing a bit further, I tried other phrases from White Robes keywords — using both whole fields and natural phrases from different fields (i.e., “strong female protagonist” and “japan adventure”). In no case did the word order seem to matter at all with regards to relevance. Nor did it seem to matter whether the phrases were taken from one field, two, or all seven.

Oh — and my freebie White Robes never ranked #1 in any search.

I’m going to assume then that, yes, all other factors being even, a book that stands to make Amazon money will tend to rank higher in searches than one that won’t. Whether relative pricing — $2.99 vs. $3.99 — is taken into account, and how much weight the Amazon algorithm gives it, I can’t even begin to guess. The answer, however, is probably a bunch. They are in the business of making money, just like the rest of us.

Conclusions: I’m shocked — shocked!

In any case, I can only assume from my further experiments that — as far as the Amazon search algorithm currently cares — natural phrases in keywords really don’t matter.

Now, having said that, I absolutely agree that what Joanna and Dave called long-tail keywords are the way to go — insofar as it’s essential to include the words your ideal reader is most likely to use in a search.

It’s clear that phrases that appear in the public metadata6 are weighted higher than those that only appear in the keywords. If, however, you start cramming your 4000-character description field with random words you think will lead to a likely search hit, not only will no one want to read your book, but Amazon will probably (and rightly) refuse to publish the keyword-stuffed description as a black-hat SEO violation.7

Finding the well-honed, long-tail8 phrases to include in the subtitle and description is essential — both for your human readers and for Amazon’s computers. As a matter of discipline, it seems to me that those ideal phrases — what I called in my last article “the question to which your book is the perfect answer” — should be the very first things you put into your KDP keyword fields. And they should definitely be prominent in all of your marketing copy — including your book description.

But it doesn’t look to me as if either the order in which you put those phrases (or the order of the words within the phrases) or the other words that are in those fields affect your book’s placement in Amazon searches at all.

Mind, I am very happy to be proven wrong. Can you think of something to test that I haven’t?

1 And read it! There’s a full transcript on the page.

2 The discussion of my article starts at around 24:43 — but I really encourage you to listen to the whole podcast. It’s extremely enlightening.

3 And if you read this, do comment below!

4 I have in fact used KDP Rocket for testing both relevance and effectiveness of KDP and AMS keywords for the past year and a half. Just for transparency’s sake. Paid for it and everything!

5 He apologized at one point for getting a bit nerdy. Didn’t bother me at all! I know you’re surprised.

6 Again: title, subtitle, series, description — oh, and author name(s) of course! (Also stuff folks will rarely search on, like ISBN.)

7 This is what’s called keyword stuffing , which Joanna refers to on the podcast. Remember back at the dawn of the internet when there were pages full of random words, sometime obscured by being the same color as the background? Yeah. You remember. That was a “black hat” (i.e., naughty) attempt to fool search engines like Google and Lycos (remember them?) into thinking the page had a lot more material on it about many more subjects than it actually did. Search engines caught on to that and banned it post haste. The white-hat art and science of making a website (or book description) most easily findable is called <Search Engine Optimization or SEO. For a very helpful book on the subject for us indie author types, see Bob Heyman’s SEO 4 Authors: Search Engine Optimization (SEO) for book authors. (Bob actually coined the term SEO.)

8 Long-tail is a marketing term, meaning something along the lines of “built for the long haul, rather than aiming for a quick result.” A long-tail marketing plan is more interested in a hundred sales next year than a hundred sales today — because if you’re still selling steadily in a year (that is, if your sales graph has a long tail), then you’ll likely continue to sell the year after that and the year after that and… In fact, as Anne Janzer pointed out at a recent meeting of Bay Area Independent Publishers Association, one of the great advantages that indie publishers have over traditional, corporate behemoths is that we’re not in a hurry; we have little to no inventory, low staff costs (unless we need to eat), low costs of delivery… Where a big publisher has to make all of its money back on the first printing or it’s in the hole, we can and should plan for the long haul — the long tail. Launch parties? Expensive release-week ads? So short-tail. ☺

Photo: BigStockPhoto